What Does Blood Libel Mean And Why Won’t It Die

- Ofek Kehila

- Nov 16, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 17, 2025

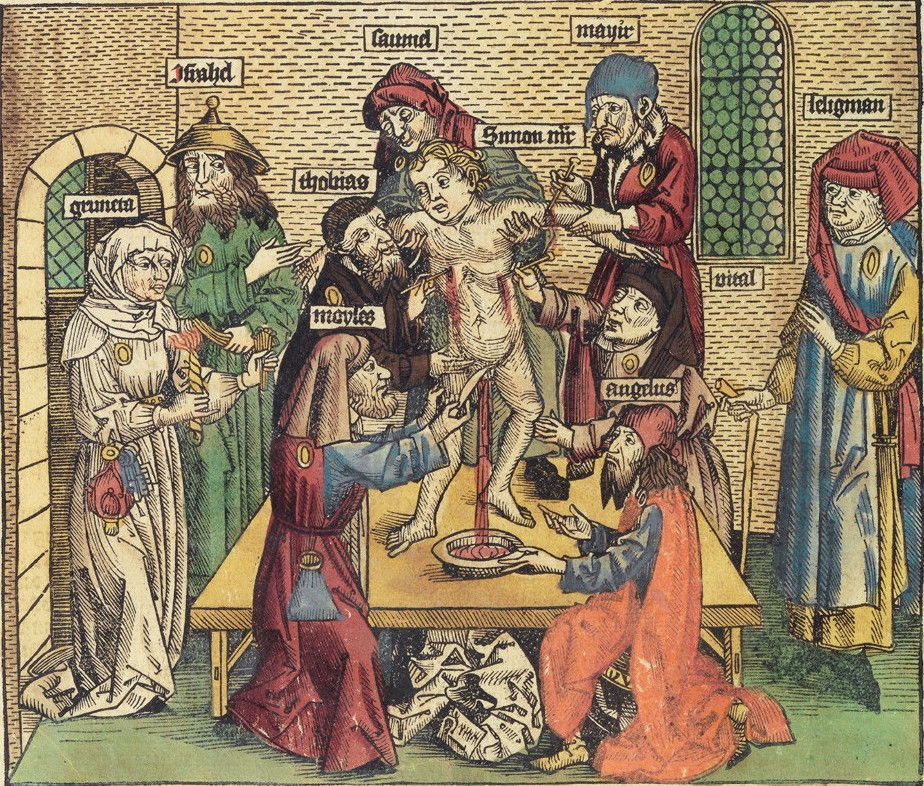

The Irish politician Conor Cruise O’Brien (1917–2008) once wrote: “There are always people around in whom anti-Semitism is a light sleeper” (The Siege: The Saga of Israel and Zionism, 1986). The undying nature of antisemitism—the hostility to or prejudice against Jewish people—is best illustrated by the infamous blood libel, an age-old accusation that Jews murder Christians to use their blood for religious rituals. What is blood libel? What forms has it taken throughout the eras and up until recent times? And why won’t one of the most graphic and brutal forms of antisemitism die centuries later?

What is blood libel?

Encyclopaedia Britannica defines “blood libel” as “the antisemitic accusation that Jews ritually sacrifice Christian children at Passover to obtain blood for unleavened bread.” According to these false accusations, Jews around the world have been murdering Christians for centuries—especially religious figures and children—and consuming the blood of their victims as part of Jewish religious rituals, such as matzah baking for Passover. Whereas the alleged victims of these “murders” have become saints and martyrs, blood libels have been historically one of the main causes of persecutions, massacres, and mass expulsions of Jewish populations. As such, the blood libel stands out as one of antisemitism’s most graphic and brutal expressions.

The blood libel today

As of today, some still consider blood libels as real historical events. Dr. Samar Maqusi of the University College London taught the Damascus Affair, which will be referred to here, as if it were an accurate depiction of events. Maqusi was recorded explaining that “During this feast, they [the Jews] make these special pancakes, or bread, and part of the holy ceremony is that drops of blood from someone who’s not Jewish, which the term is ‘gentile,’ has to be mixed in that bread.”

Far from debunking the blood libel, Maqusi described it as a possibly real historical account. Consequently, the University College London launched an investigation and banned her from campus. The university president and provost, Dr. Michael Spence, said he was utterly appalled by Maqusi’s heinous antisemitic comments: “Antisemitism has absolutely no place in our university, and I want to express my unequivocal apology to all Jewish students, staff, alumni, and the wider community that these words were uttered at UCL.”

Blood libels: Historical examples

Whereas antisemitism is as old as Judaism itself, the roots of blood libel can be traced back to the 12th century. Since then, false accusations of ritual murders by Jews have circulated the world, reappearing again and again through the centuries.

The following are only a few of the libel’s grim expressions throughout history:

Although false accusations against Jews have prevailed since antiquity, historians locate the first blood libel in 12th-century England, and more specifically, in the case of William of Norwich, an apprentice from the city of Norwich who was murdered during Easter 1144. William’s murder was never truly solved, but the city’s Jewish community was immediately blamed for it. According to the libel, the twelve-year-old Christian boy was bought by the Jews, who then tortured and crucified him. The myth was divulged by a monk of Norwich’s priory, and in the years that followed, a cult was developed around William of Norwich. For their part, the Jews of England were constantly blamed for his death and that of other Christian children. Eventually, blood libels in England led to the massacres at London, Bury, and York (1189–1190), where many Jews were attacked and brutally murdered by crusaders and rioting mobs.

A century after these events had taken place, a second major blood libel emerged in England. In 1255, the death of a nine-year-old boy named Hugh in the city of Lincoln was falsely blamed on the Jewish community. The accusations were very similar to those of the Norwich libel: abduction, torture, and brutal crucifixion. As a result, some 90 Jews were arrested and tried for ritual murder, 18 of whom were hanged. “Little Saint Hugh” became a local saint, and his myth lived on in literature, appearing in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (“The Prioress’s Tale”). Roughly 35 years after these events, Jews were expelled from all of England (1290).

In 1490, six Conversos (Jews converted to Christianity) and two Jews, all inhabitants of La Guardia, Spain, were tried by the Inquisition under the false accusation of murdering a Christian child and extracting his heart for acts of sorcery. As an immediate consequence, the accused were burned at the stake. Two years later, the entirety of the Jewish community was expelled from Spain (1492). This myth, too, found its way into antisemitic art, serving as the basis of the play El niño inocente de La Guardia by Lope de Vega.

In 1840, the Italian monk Father Thomas and his Muslim servant disappeared in the Jewish quarter of Damascus. Soon after, the local Jewish community was accused of murdering the monk and extracting his blood to bake matzot, the Passover bread. Several Jews were tortured until they forcibly confessed to the murder, and others died during the interrogation. In the aftermath of the affair, antisemitism rose once again in the Ottoman Empire, and Jews were attacked by Muslims and Christians alike.

In 1928, the Jews of the city of Massena, New York, were falsely accused of the kidnapping and ritual murder of four-year-old Barbara Griffiths. Even though the girl was found alive and well later on, the citizens of Massena continued to accuse the Jewish community of her kidnapping.

Why won’t blood libel die?

It seems that as long as Jewish people draw breath, antisemitism and its brutal expression, the blood libel, are here to stay. The libels of Norwich, Lincoln, La Guardia, Damascus, and Massena are only a few illustrative examples of a world-encompassing, age-old phenomenon: blood libels appeared almost everywhere and at any time, from medieval England to early-modern Spain, 20th-century United states, Nazi Germany, and more recently, Syria (2003), Saudi Arabia (2012), and Egypt (2013).

Historically, not only have blood libels caused hostility, persecution, and massacres of Jews around the globe, but they are also responsible for at least two of the biggest expulsions of Jewish communities: those of England (1290) and Spain (1492).

In recent times, blood libels have been related to Zionism, the state of Israel, and the war in Gaza. It is not far-fetched to claim that the October 7 massacre committed by Hamas is a direct consequence of antisemitic propaganda not too different from the traditional libels. Blood libels won’t die because “there are always people around in whom antisemitism is a light sleeper.” What can be done is to counter it via fact-checking, debunking myths, and educating for tolerance.

Ofek Kehila (Israel, 1987) is a scholar of Spanish Golden Age literature and Latin American literature of the 20th and 21st centuries. His research bridges the gap between those traditions, highlighting their aesthetic, cultural, and historical dialogue. He holds a PhD from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2022) and was a postdoctoral fellow at Freie Universität Berlin (2023-2025).